4.09 Now, Later

Kate Doyle

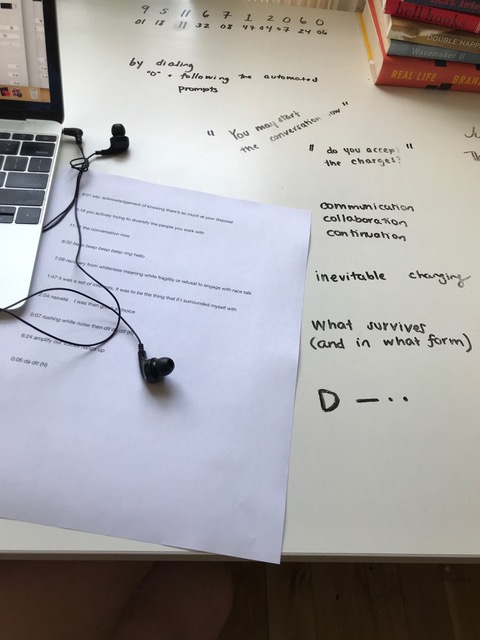

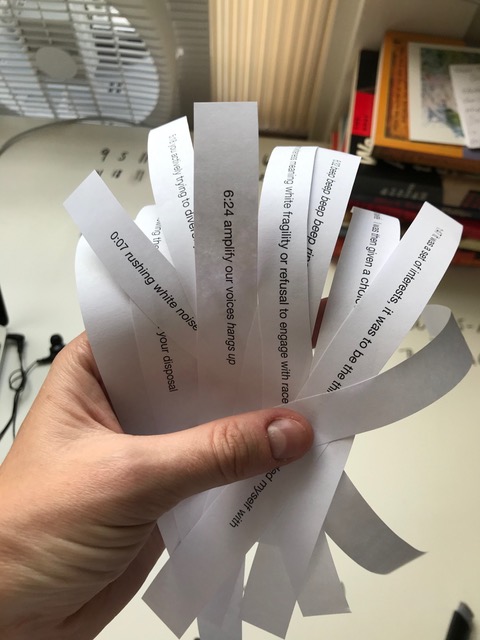

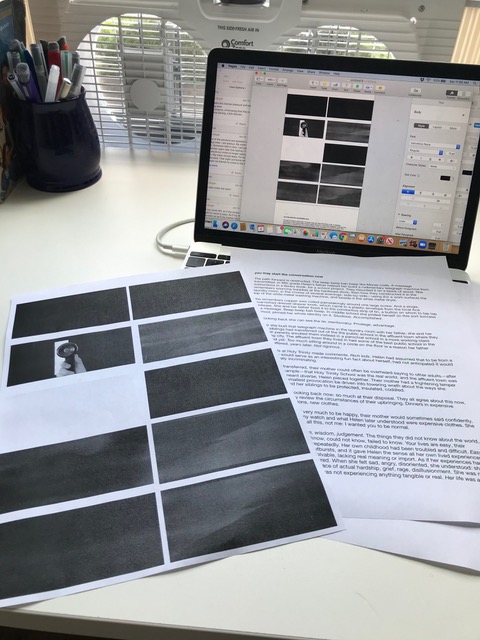

The path forward is obstructed. And backward, memory: the beep beep bah beep of a transmission in Morse code. In fifth grade, this was the subject of Helen’s school project: Samuel Morse, the invention of the telegraph. Innovation, technological progress, communication across great distances, the promise of the future. In the laundry room, her father helped her build a rudimentary telegraph machine from instructions she found in a library book. They mounted it on a block of wood.

She remembers sourcing supplies at the hardware store, then how they constructed it in the course of several evenings, side-by-side—using, for a work surface, the tops of the white metal washing machine and dryer. She remembers the long wire they coiled painstakingly around a large screw. And the single, unvarnished dresser-drawer knob, which came in a plastic envelope from the craft aisle. With her father’s help she affixed it to the conductive strip of tin: a button on which to tap-tap out a message. Telegraph key was the technical term, said the library book. Beep beep bah beep.

In middle school she prided herself on academic success of this sort, pinned her whole identity on it. Studious. Accomplished. Now looking back, she can see the lie: meritocracy.

The year she built the telegraph in the laundry room, she and her younger siblings had been transferred out of the public school in the wealthy town where they lived. Their parents enrolled them in a Catholic school in the more working-class neighboring city. The wealthy town boasted some of the best public schools in the country, and yet: Too much sitting around in a circle on the floor is a rationale her father eventually offered, years later, for transferring them. Overemphasis on feelings. Not rigorous. We wanted you to experience discipline.

Helen had assumed that to be from a different town would serve as an interesting fun fact about herself in this new environment. Her first day of school, she kept telling people, but noticed how it seemed to be received as something fundamentally dubious. In time, the other kids at Holy Trinity made comments. Rich kids. White kids.

In this year when they transferred schools, their mother could often be overheard saying to other adults—after playdates, for example—that Holy Trinity School was the real world, and the affluent town was not. By this she seemed to mean diverse—a euphemistic word. Their mother always had a frightening temper and could at the smallest provocation be driven into towering wrath about the ways she perceived Helen and her siblings to be protected, insulated, coddled. And this feels true, looking back: so much at their disposal. Helen and her siblings all agree about this now, years later, when they review the circumstances of their upbringing. Dinners in expensive restaurants, ski vacations. Personally I don’t need very much to be happy, their mother would sometimes say confidently, though she wore a Tiffany watch and always dressed in what Helen later understood were expensive clothes. She said, Your father wanted all this, not me: I wanted you to be normal.

Naiveté. Helen, in fifth grade, looked it up in the dictionary they kept on a table at the top of the stairs: lack of experience, wisdom, judgement. The things she and her siblings did not know about the world, or didn’t know they didn’t know, could not know, failed to know.

Your lives are easy, their mother said bitterly, again and again. Her own childhood had been troubled, and easy was her refrain, an accusation. It gave Helen the curious sense that her own personal lived experiences were artificial, dissolvable, lacked real meaning or import, perhaps had not actually occurred. Any time she felt sad, angry, disoriented, she understood: she was scratching the surface of actual hardship, grief, rage. She was experiencing nothing of normal life, nothing tangible or real. Her life was a set of protections. It had no stakes. This was her childhood: a meaningless exercise, a trial run. Devoid. Lucky. Fortunate. She could mess up anything with no actual result.

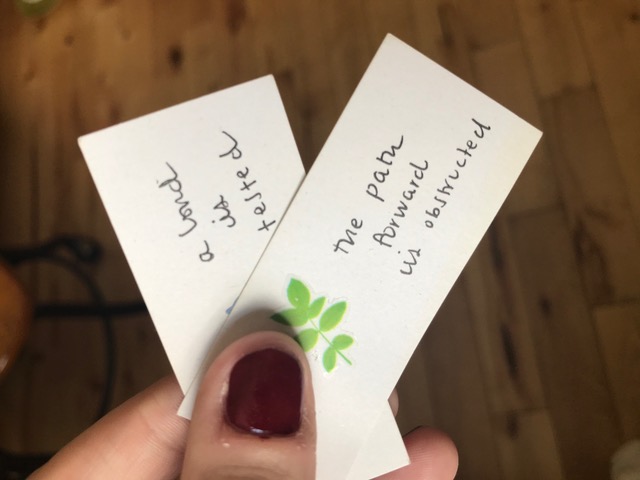

She can begin to see this over the years, and now. This is the necessary work, you have to try to see it clearly. Beep beep beep beep beep ring HELLO? You need to start the conversation now. A bond is being tested, what are you going to do about it? Do you see now what you have been a part of? Do you accept the charges leveled against you?

Once, before they had children—when her mother’s life was beginning to become easy, when she had married someone who was making all this money—Helen’s parents spent a year living in France. At some point Helen demanded to know, longed for some explanation: why exactly did they ever come back? Why did they choose the bland affluent town over living abroad? Because in America there is real upward mobility, said her father. Anyone can pull themselves up by their bootstraps. In Europe you are trapped in the circumstances you were born to. I missed that sense of opportunity for everyone. I hated the sense of predetermination.

But this is a lie. She keeps trying to help him understand, now. Propaganda, mythology. Fundamental dubiousness. She was predetermined to get an A on her telegraph project, her mother to wear a Tiffany watch. We are an exceptional country, he says. Communication across great distances, promises of the future. We aren’t, Helen says. We aren’t, says her mother. We aren’t, say her siblings. Do you see now what we have been a part of? Can you see it?